This originally appeared in WORN Fashion Journal issue 3 and was reprinted in The WORN Archive: A Fashion Journal about the Arts, Ideas, and History of What We Wear.

I got to discuss the book on New Hampshire Public Radio’s Word of Mouth.

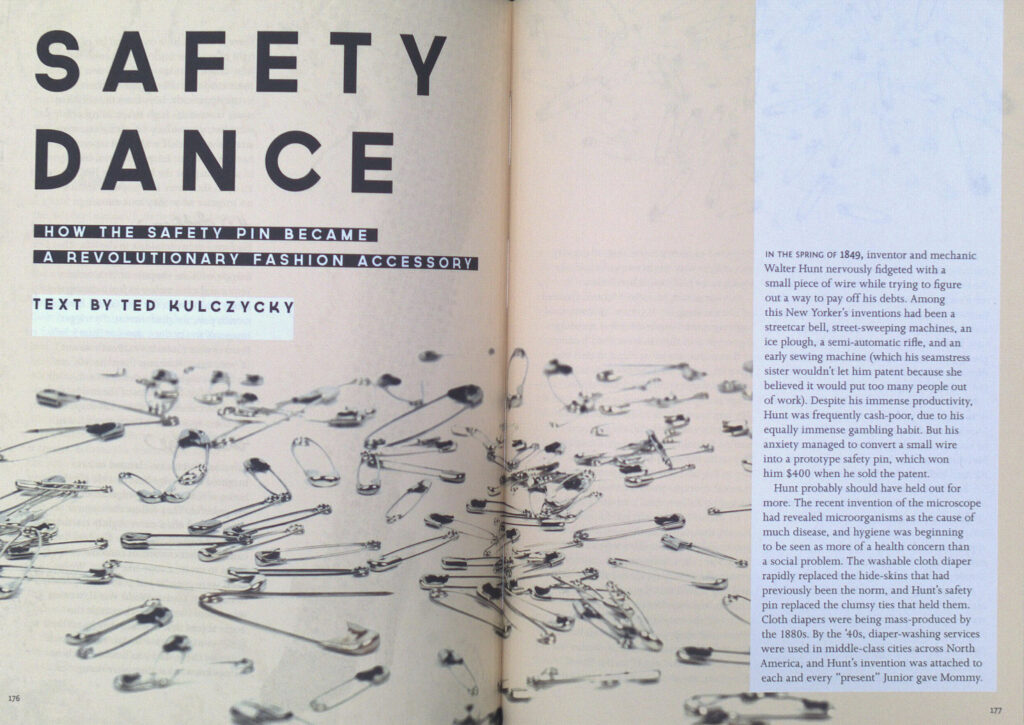

SAFETY DANCE

How the safety pin became a revolutionary fashion accessory.

Text by Ted Kulczycky

In the spring of 1849, inventor and mechanic Walter Hunt nervously fidgeted with a small piece of wire while trying to figure out a way to pay off his debts. Among this New Yorker’s inventions had been a streetcar bell, street-sweeping machines, an ice plough, a semi-automatic rifle, and an early sewing machine (which his seamstress sister wouldn’t let him patent because she believed it would put too many people out of work). Despite his immense productivity, Hunt was frequently cash-poor, due to his equally immense gambling habit. But his anxiety managed to convert a small wire into a prototype safety pin, which won him $400 when he sold the patent.

Hunt probably should have held out for more. The recent invention of the microscope had revealed microorganisms as the cause of much disease, and hygiene was beginning to be seen as more of a health concern than a social problem. The washable cloth diaper rapidly replaced the hide-skins that had previously been the norm, and Hunt’s safety pin replaced the clumsy ties that held them. Cloth diapers were being mass-produced by the 1880s. By the ’40s, diaper-washing services were used in middle-class cities across North America, and Hunt’s invention was attached to each and every “present” Junior gave Mommy.

But the introduction of the feminine sanitary napkin gave parents ideas, and by the early ’60s, a number of disposable diapers were on the market. By the mid-’70s, Pampers basically eradicated their cloth counterparts, and the safety pin was replaced by sticky tape. At around the same time, however, a young poet-musician-addict accidentally discovered same new uses for Hunt’s safety pin: political statement and fashion object.

Richard Meyers moved to New York City in the late ’60s with his prep-school chum, Tom Miller. After several years of working in bookstores and operating a small press, Meyers and Miller changed their names to Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine and formed the band Television. Unlike most bands of the era, Television wore their everyday clothes when they performed. Hell’s filthy unkempt hair and generally dishevelled appearance had already made an impression before he arrived at punk mecca CBGB, his shredded t-shirt held together by safety pins.

Hell has long maintained that this wasn’t meant to be any kind of statement, but was simply a way of holding his clothes together. This explanation has never really made much sense: why not just wear another shirt? Photographer and friend Bob Gruen filled in the missing details. What Hell neglected to mention was that, after a very recent fight with his live-in girlfriend, she took a razor blade to all his clothes.

As it happened, Malcolm McLaren (husband of fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and aspiring music impresario) was spending a good deal of time in New York, looking to find musicians to steal and to steal from. His plan was to package his Dadaist politics with his wife’s confrontational fashion sense and graft them on to a prepackaged ’70s boy band (think of The Osmonds or the Bay City Rollers). Although he was unable to mold any New York musicians to exactly his ideal, he returned to his native England full of fashion notes and musical concepts from the New York scene, including Richard Hell’s unique garb.

By mid-1975, McLaren had formed the Sex Pistols, drawing from the disenfranchised youth who hung out at his wife’s boutique. Sex (later called Seditionaries). Littered among the S/M garb, spray-painted t-shirts, and dog collars that the band wore were clothes held together by safety pins.

One of the employees at the McLaren-Westwood shop was Jordan (born Pamela Crooke). By common consent, Jordan was not only the first “punk” in the United Kingdom, she was also its most consistent media image. Virtually every British television report and newspaper story that appeared on punk in the late ’70s featured an image of Jordan in her suggestive outfits with cropped and sculpted dayglo hair.

Much credit is due her for defining punk’s image, but she often claims to have also invented the safety pin as fashion statement. “Johnny (Rotten, lead singer of the Sex Pistols) always tells the story of how he went into Sex one day – I had on this T-shirt with a big rip right across the front, so I’d put in a safety pin to cover it up. Johnny thought it was great, and the safety pin thing started there and then.”

Since both McLaren and Rotten dispute this account (and give proper credit to

Richard Hell), Jordan’s memory seems faulty. However, she may have been the first to use a safety pin as jewelry. There are pictures of her in the early punk era with safety pins piercing various parts of her body, whereas the other punks from that era seem relatively unscathed. By the late ’70s, this was standard practice among aspiring punks. There were (unsubstantiated) rumours that certain clubs had “dress codes” requiring piercings. If

you showed up without the appropriate gear, the doorman conveniently had a safely pin and pencil eraser (but no antiseptic ointment) ready to improve your image.

By the early ’90s, punk had morphed into grunge and “alternative,” and the days of mohawks and safety pins seemed as quaint as ducktails and zoot suits. The late-night drunken bathroom piercings of yesteryear gave way to midday drunken visits to “body artist” boutiques. The stainless steel barbell became the standard starter piece.

Of course, the safety pin continues to be used as an ad hoc clothing mender and fastener for badges and buttons. But as a symbol, the safety pin is no longer dangerous. It is worn like a support ribbon to promote patient safety measures in the medical industry, and every September 10, many American schools celebrate Safety Pin Day.

But in the spring of 2005, Vivienne Westwood launched her “Hardcore Diamonds” jewelry line. For the low starting price of $400, any street punk could use a gold safety pin (with a .05-karat diamond setting) to hold their ratty t-shirt together, Perhaps, if he were alive today, Walter Hunt would use the $400 he received for inventing the safety pin to purchase one of these must-have fashion items.