Here is a pretty scholarly piece I wrote about Do the Right Thing. It’s title is, and always has been, BY ANY MEANINGS NECESSARY. The play on words (whether or not it was as clever as I thought) was intended as a comment on academic postmodernism and the difference between the nature of political activism in the 1960s vs the 1980s. Much to my frustration, this article is often mistitled online as BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY, which is a simple unnuanced reference to a famous Malcom X quote.

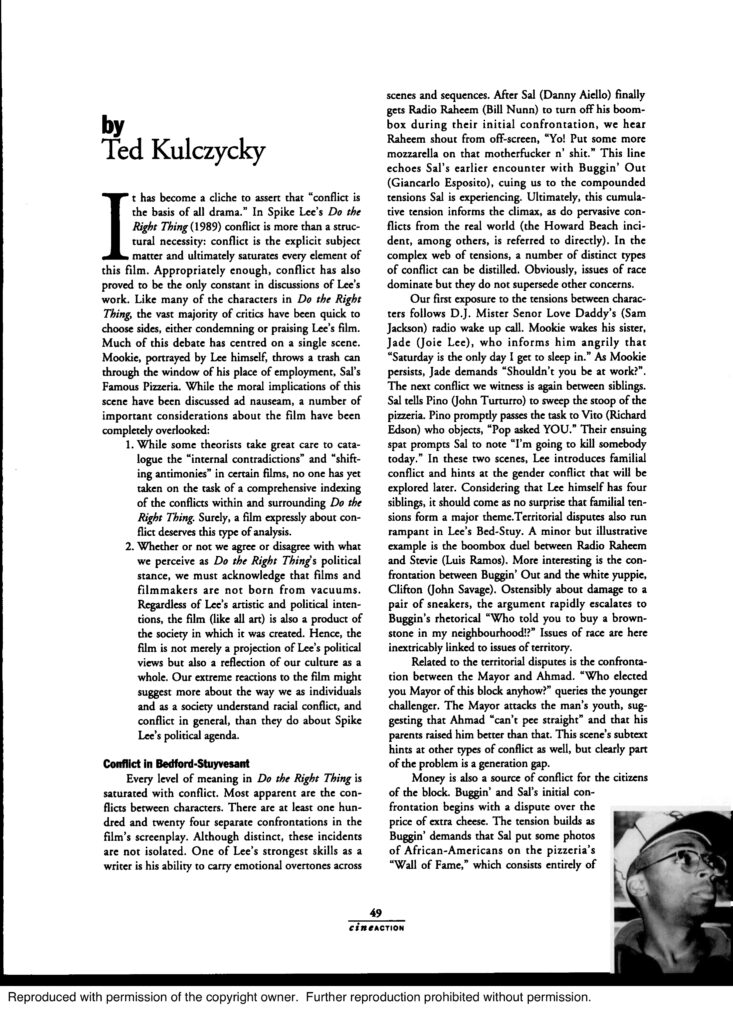

It has become a cliche to assert that “conflict is the basis of all drama.” In Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) conflict is more than a structural necessity: conflict is the explicit subject matter and ultimately saturates every element of this film. Appropriately enough, conflict has also proved to be the only constant in discussions of Lee’s work. Like many of the characters in Do the Right Thing, the vast majority of critics have been quick to choose sides, either condemning or praising Lee’s film. Much of this debate has centred on a single scene. Mookie, portrayed by Lee himself, throws a trash can through the window of his place of employment, Sal’s Famous Pizzeria. While the moral implications of this scene have been discussed ad nauseam, a number of important considerations about the film have been completely overlooked:

1. While some theorists take great care to catalogue the “internal contradictions” and “shifting antimonies” in certain films, no one has yet taken on the task of a comprehensive indexing of the conflicts within and surrounding Do the Right Thing. Surely, a film expressly about conflict deserves this type of analysis.

2. Whether or not we agree or disagree with what we perceive as Do the Right Thing‘s political stance, we must acknowledge that films and filmmakers are not born from vacuums. Regardless of Lee’s artistic and political intentions, the film (like all an) is also a product of the society in which it was created. Hence, the film is not merely a projection of Lee’s political views but also a reflection of our culture as a whole. Our extreme reactions to the film might suggest more about the way we as individuals and as a society understand racial conflict, and conflict in general, than they do about Spike Lee’s political agenda.

Conflict in Bedford-Stuyvesant

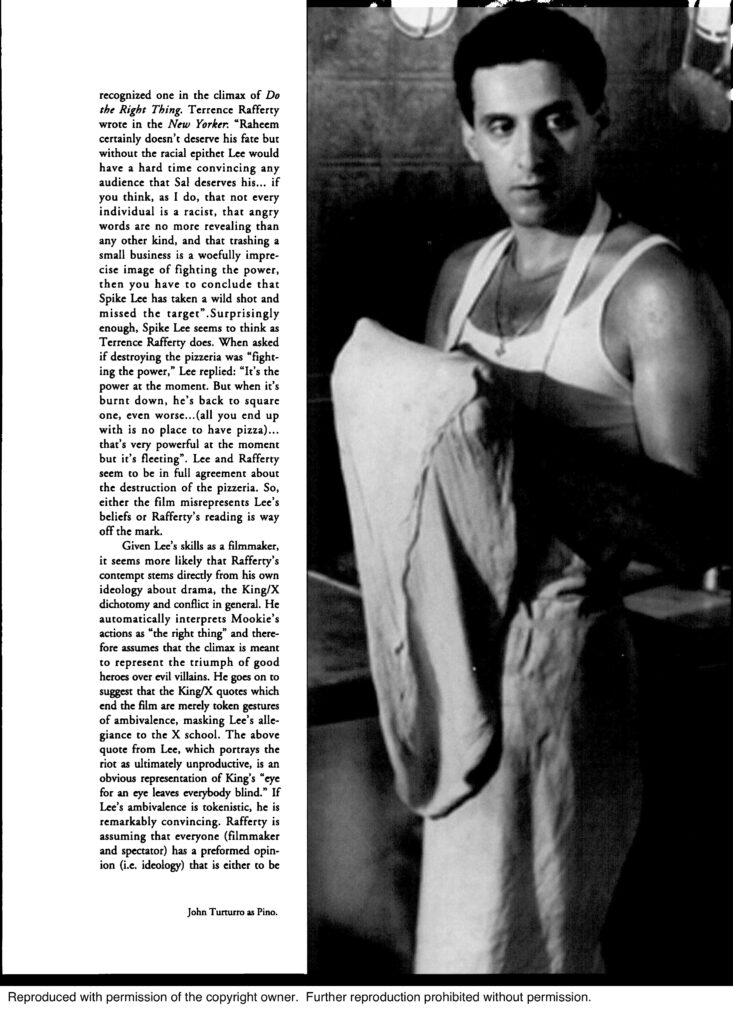

Every level of meaning in Do the Right Thing is saturated with conflict. Most apparent are the conflicts between characters. There are at least one hundred and twenty four separate confrontations in the film’s screenplay. Although distinct, these incidents are not isolated. One of Lee’s strongest skills as a writer is his ability to carry emotional overtones across scenes and sequences. After Sal (Danny Aiello) finally gets Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) to turn off his boombox during their initial confrontation, we hear Raheem shout from off-screen, “Yo! Put some more mozzarella on that motherfucker n’ shit.” This line echoes Sal’s earlier encounter with Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), cuing us to the compounded tensions Sal is experiencing. Ultimately, this cumulative tension informs the climax, as do pervasive conflicts from the real world (the Howard Beach incident, among others, is referred to directly). In the complex web of tensions, a number of distinct types of conflict can be distilled. Obviously, issues of race dominate but they do not supersede other concerns.

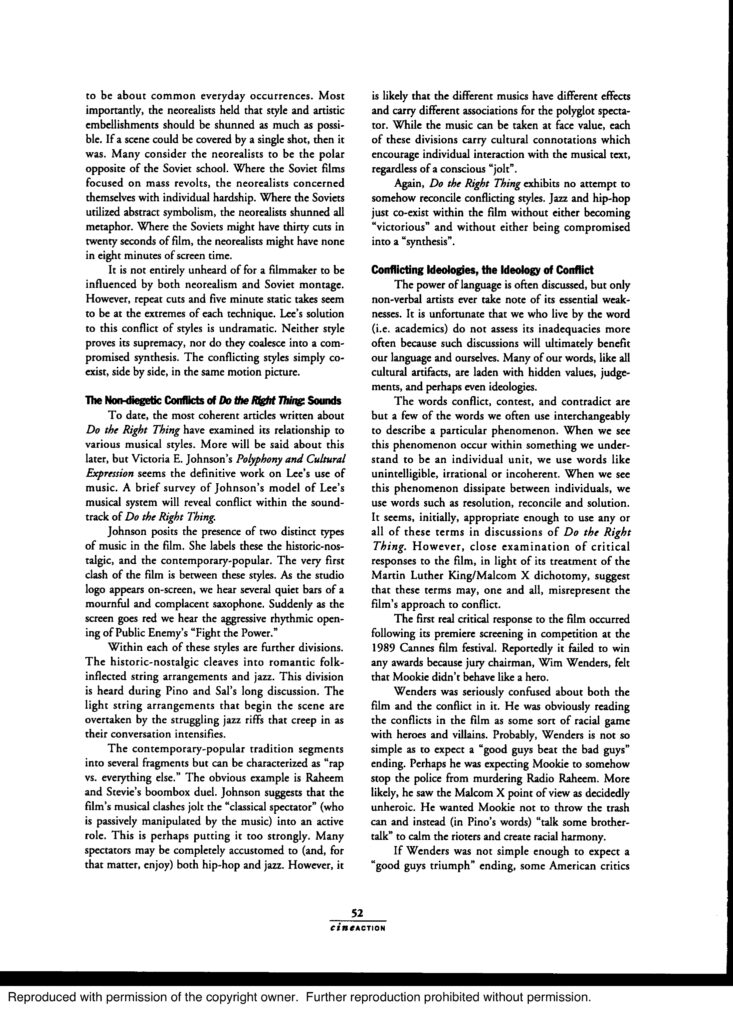

Our first exposure to the tensions between characters follows D.J. Mister Senor Love Daddy’s (Sam Jackson) radio wake up call. Mookie wakes his sister, Jade (Joie Lee), who informs him angrily that “Saturday is the only day I get to sleep in.” As Mookie persists, Jade demands “Shouldn’t you be at work?”. The next conflict we witness is again between siblings. Sal tells Pino (John Turturro) to sweep the stoop of the pizzeria. Pino prompdy passes the task to Vito (Richard Edson) who objects, “Pop asked YOU.” Their ensuing spat prompts Sal to note “I’m going to kill somebody today.” In these two scenes, Lee introduces familial conflict and hints at the gender conflict that will be explored later. Considering that Lee himself has four siblings, it should come as no surprise that familial tensions form a major theme.Territorial disputes also run rampant in Lee’s Bed-Stuy. A minor but illustrative example is the boombox duel between Radio Raheem and Stevie (Luis Ramos). More interesting is the confrontation between Buggin’ Out and the white yuppie, Clifton (John Savage). Ostensibly about damage to a pair of sneakers, the argument rapidly escalates to Buggin’s rhetorical “Who told you to buy a brownstone in my neighbourhood!?” Issues of race are here inextricably linked to issues of territory.

Related to the territorial disputes is the confrontation between the Mayor and Ahmad. “Who elected you Mayor of this block anyhow?” queries the younger challenger. The Mayor attacks the man’s youth, suggesting that Ahmad “can’t pee straight” and that his parents raised him better than that. This scene’s subtext hints at other types of conflict as well, but clearly part of the problem is a generation gap.

Money is also a source of conflict for the citizens of the block. Buggin’ and Sal’s initial confrontation begins with a dispute over the price of extra cheese. The tension builds as Buggin’ demands that Sal put some photos of African-Americans on the pizzeria’s “Wall of Fame,” which consists entirely of Italian-Americans: “Since we spend much money in here we do have some say.” When Sal refuses, Buggin’ attempts to organize a boycott in the hope that economic pressure will change Sal’s mind.

Sexual tension is also in evidence, although not as explicitly as in some of Lee’s other films. Sal’s painfully obvious flirtations with Jade evoke negative reactions from both Pino and Mookie, as we can tell from a tracking shot of the identical expressions on their faces. Mother Sister’s (Ruby Dee) insults eventually become a form of flirtation as her relationship with the Mayor improves. Mookie’s relationship with Tina (Rosie Perez) is portrayed as passionate but strained, due to Mookie’s difficulty in accepting his responsibilities. Both Tina and Jade repeatedly remind Mookie that he has commitments that he must try to live up to. Although Lee portrays some of his characters within the gendered stereotypes of “women as responsible nags” vs. “men as irresponsible good-for-nothings,” he weaves these questions of responsibility more deeply into the film’s conflictive network.

Most of Sal’s confrontations with Mookie stem from Mookie’s disregard for his responsibilities as an employee. Buggin’s exhortation to “Stay Black” is intended to remind Mookie that he has obligations that may take priority over his commitment to his employer. Both the title of the film and its climax relate to questions of responsibility. Had any of the characters involved in the climax behaved more responsibly, Radio Raheem’s death (and therefore the destruction of Sal’s pizzeria) could have been avoided. Sal could have put African-Americans on the wall, or been slower to reach for his baseball bat. Buggin” Out could have been, as Jade puts it, “down for something positive in the community.” Mookie might have actually become involved in the dispute while there was still a chance of diffusing the tension. Sal could have politely asked Raheem to turn down the music. Instead he bellows, “No service until you turn that shit off.” Indeed, on any day other than the hottest of the year, the fate of these characters may have been quite different. As Lee notes in his pre-production journal, “It’s been my observation that when the temperature rises beyond a certain point, people lose it…the heat makes everything explosive, including the racial climate.” The characters are, in a sense, engaged in a conflict with the environment itself.

The Non-diegetic Conflicts of Do Me Right Thing: Sights

One of the few aspects of Lee’s work that is not the subject of fierce debate is his working familiarity with a wide variety of cinematic techniques, as well as his willingness to experiment with them undogmatically. Lee used to deny stylistic influences beyond Jarmusch, Scorsese and Van Peebles, but has recently confessed a surprising fondness for such films as Help! (1965, Richard Lester) and A Face in the Crowd (1957, Elia Kazan). Lee’s wide range of influences is perhaps most evidenced in Do the Right Thing.

Expressionist influences are exhibited in the film’s opening dance sequence. The stylized two-dimensional backdrop combines with high contrast (yet colourful) lighting to evoke the horrible worlds of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) and Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Of course, many expressionist codes have been adopted by mainstream music videos and because of this their use here seems less anachronistic than some of Lee’s other techniques.

Contrasting the expressionism is Lee’s use of the conventional codes of realism. In most scenes, Lee obeys the dictums of the classic Hollywood continuity editing style. Eyelines always match; the axis of action is usually obeyed (barring a new establishing shot); dialogue is often covered in the “shot/reverse shot” manner. The finer points of the style are also in evidence. Tradition has it that cuts should be “smooth” and not jar the eye of the spectator. Thus, when cutting between two shots of the same subject, image size and/or camera angle should change so the change is not perceived as the mere absence of frames, or a “jump”. Our introduction to “the corner men” begins with an extreme long shot, then cuts to a long shot and finally ends on a medium three-shot. Although he does not change the angle, Lee smooths the cuts by using the passing cars as wipes. Lee does not restrict the film’s realism to the editing. While we are concentrating on the activity inside Sal’s, a passing glance through the window will reveal other recognizable characters going about their business on the street. This passive use of deep-focus photography reinforces the sense of a real world, which exists with or without the direct attention of the camera.

A multitude of hand-held and zoom shots appeal to codes of ultra-realism familiar from documentaries. One might expect this style to clash violently with the classical cutting habits, but Lee somehow manages to get them to hang together. When Sal asks Mookie to remove Buggin’ from the pizzeria, the camera that had provided the establishing medium shot follows the two out the door. After their conversation on the street the camera pulls back into the pizzeria, following Mookie. It comes to rest in a new position, thus providing a new establishing shot. A conversation between Sal, Pino and Mookie ensues and subsequent cuts obey the new axis of action.

The illusion of reality is partially broken by a string of direct addresses to the camera. A quick zoom forward introduces the slanderous soliloquies. As Mookie, Pino, Stevie, the Policeman, and Sonny deliver in turn their hateful speeches, the camera holds fast, dead on. This direct address seems inspired by Jean Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967), but is also reminiscent of Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1968). Certainly, Radio Raheem’s similarly-shot speech regarding love and hate was inspired by Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter (1955). Whatever the sources, Lee’s break with traditional realism has an atypical effect in this sequence. Due to the build up of tension throughout the course of the narrative, we experience a sense of mounting alienation (parallel to that of the characters) and thus anticipate a cathartic release. These racist rants satisfy our expectations, while their crudity increases the overall tone of alienation. The usual effect of this type of break from realism is simply the subversion of audience expectation as a reminder of film’s constructed nature. Here, Lee’s use of the direct address actually fuels our involvement with the narrative, at the same time as it makes us uncomfortable with our character empathization.

Love and hate figure in the most drastically conflicting of Lee’s styles. Lee uses a number of techniques inspired by 1920’s Soviet filmmakers. Montage sequences are now common currency in virtually every style of filmmaking, and Lee’s use of them merits no special attention. More subtle techniques, such as Eisenstein’s “Rhythmic Montage” have also found their way into many types of film. However, “repeat cuts” have enjoyed but two brief resurgences (in Godard and Music Videos) and have never really been explored enough to better Eisenstien’s delicate use of them in Battleship Potemkin (1925). By 1989, even MTV had deemed them passe and it seems odd that two of them appear in Do the Right Thing. One occurs upon Mookie’s reunion with Tina. We see the same shot of their kiss twice in quick succession. After Mookie yells “HATE!”, we see the projectile trash can break through the pizzeria window twice (although from different shots). These doublings are used (like the repeat cuts in Potemkin regarding revolutionary consciousness) to accentuate decisive action (here regarding love and hate).

Lee’s film also contains a number of “long takes.” Most notable is a six-minute scene that occurs precisely at the film’s midpoint. Sal and Pino discuss the future of their business in the window of the pizzeria.The sixminute scene is covered by a single shot that begins with a brief zoom in. Although often associated with Welles, the long take style is usually considered to have reached its zenith in the work of the Italian neorealists. Their over-arching aesthetic demanded that cinema be ultra-real. Characters had to be human, and plots had to be about common everyday occurrences. Most importantly, the neorealists held that style and artistic embellishments should be shunned as much as possible. If a scene could be covered by a single shot, then it was. Many consider the neorealists to be the polar opposite of the Soviet school. Where the Soviet films focused on mass revolts, the neorealists concerned themselves with individual hardship. Where the Soviets utilized abstract symbolism, the neorealists shunned all metaphor. Where the Soviets might have thirty cuts in twenty seconds of film, the neorealists might have none in eight minutes of screen time.

It is not entirely unheard of for a filmmaker to be influenced by both neorealism and Soviet montage. However, repeat cuts and five minute static takes seem to be at the extremes of each technique. Lee’s solution to this conflict of styles is undramatic. Neither style proves its supremacy, nor do they coalesce into a compromised synthesis. The conflicting styles simply coexist, side by side, in the same motion picture.

The Non-diegetic Conflicts of Do the Right Thing Sounds

To date, the most coherent articles written about Do the Right Thing have examined its relationship to various musical styles. More will be said about this later, but Victoria E. Johnson’s “Polyphony and Cultural Expression” seems the definitive work on Lee’s use of music. A brief survey of Johnson’s model of Lee’s musical system will reveal conflict within the soundtrack of Do the Right Thing.

Johnson posits the presence of two distinct types of music in the film. She labels these the historic-nostalgic, and the contemporary-popular. The very first clash of the film is between these styles. As the studio logo appears on-screen, we hear several quiet bars of a mournful and complacent saxophone. Suddenly as the screen goes red we hear the aggressive rhythmic opening of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.”

Within each of these styles are further divisions. The historic-nostalgic cleaves into romantic folkinflected string arrangements and jazz. This division is heard during Pino and Sal’s long discussion. The light string arrangements that begin the scene are overtaken by the struggling jazz riffs that creep in as their conversation intensifies.

The contemporary-popular tradition segments into several fragments but can be characterized as “rap vs. everything else.” The obvious example is Raheem and Stevie’s boombox duel. Johnson suggests that the film’s musical clashes jolt the “classical spectator” (who is passively manipulated by the music) into an active role. This is perhaps putting it too strongly. Many spectators may be completely accustomed to (and, for that matter, enjoy) both hip-hop and jazz. However, it is likely that the different musics have different effects and carry different associations for the polyglot spectator. While the music can be taken at face value, each of these divisions carry cultural connotations which encourage individual interaction with the musical text, regardless of a conscious “jolt”.

Again, Do the Right Thing exhibits no attempt to somehow reconcile conflicting styles. Jazz and hip-hop just co-exist within the film without either becoming “victorious” and without either being compromised into a “synthesis”.

Conflicting Ideologies, the Ideology of Conflict

The power of language is often discussed, but only non-verbal artists ever take note of its essential weaknesses. It is unfortunate that we who live by the word (i.e. academics) do not assess its inadequacies more often because such discussions will ultimately benefit our language and ourselves. Many of our words, like all cultural artifacts, are laden with hidden values, judgements, and perhaps even ideologies.

The words conflict, contest, and contradict are but a few of the words we often use interchangeably to describe a particular phenomenon. When we see this phenomenon occur within something we understand to be an individual unit, we use words like unintelligible, irrational or incoherent. When we see this phenomenon dissipate between individuals, we use words such as resolution, reconcile and solution. It seems, initially, appropriate enough to use any or all of these terms in discussions of Do the Right Thing, However, close examination of critical responses to the film, in light of its treatment of the Martin Luther King/Malcom X dichotomy, suggest that these terms may, one and all, misrepresent the film’s approach to conflict.

The first real critical response to the film occurred following its premiere screening in competition at the 1989 Cannes film festival. Reportedly it failed to win any awards because jury chairman, Wim Wenders, felt that Mookie didn’t behave like a hero.

Wenders was seriously confused about both the film and the conflict in it. He was obviously reading the conflicts in the film as some sort of racial game with heroes and villains. Probably, Wenders is not so simple as to expect a “good guys beat the bad guys” ending. Perhaps he was expecting Mookie to somehow stop the police from murdering Radio Raheem. More likely, he saw the Malcom X point of view as decidedly unheroic. He wanted Mookie not to throw the trash can and instead (in Pino’s words) “talk some brothertalk” to calm the rioters and create racial harmony.

If Wenders was not simple enough to expect a “good guys triumph” ending, some American critics recognized one in the climax of Do the Right Thing. Terrence Rafferty wrote in the New Yorker. “Raheem certainly doesn’t deserve his fate but without the racial epithet Lee would have a hard time convincing any audience that Sal deserves his… if you think, as I do, that not every individual is a racist, that angry words are no more revealing than any other kind, and that trashing a small business is a woefully imprecise image of fighting the power, then you have to conclude that Spike Lee has taken a wild shot and missed the target”. Surprisingly enough, Spike Lee seems to think as Terrence Rafferty does. When asked if destroying the pizzeria was “fighting the power,” Lee replied: “It’s the power at the moment. But when it’s burnt down, he’s back to square one, even worse…(all you end up with is no place to have pizza)… that’s very powerful at the moment but it’s fleeting”. Lee and Rafferty seem to be in full agreement about the destruction of the pizzeria. So, either the film misrepresents Lee’s beliefs or Rafferty’s reading is way off the mark.

Given Lee’s skills as a filmmaker, it seems more likely that Rafferty’s contempt stems direcdy from his own ideology about drama, the King/X dichotomy and conflict in general. He automatically interprets Mookie’s actions as “the right thing” and therefore assumes that the climax is meant to represent the triumph of good heroes over evil villains. He goes on to suggest that the King/X quotes which end the film are merely token gestures of ambivalence, masking Lee’s allegiance to the X school. The above quote from Lee, which portrays the riot as ultimately unproductive, is an obvious representation of King’s “eye for an eye leaves everybody blind.” If Lee’s ambivalence is tokenistic, he is remarkably convincing. Rafferty is assuming that everyone (filmmaker and spectator) has a preformed opinion (i.e. ideology) that is either to be projected (for the filmmaker) or reinforced (for the spectator). In Rafferty’s vision, no one is allowed the privilege of confusion, doubt, or open-mindedness.

Lee’s supporters can be equally simplistic. Although none has suggested that Lee fells into the King camp, a number of critics believe the film portrays a compromising “synthesis” of the King and X views. James Hurst suggests that Mookie’s toss of the trash can both saves Sal’s life, and sparks the riot that destroys the “endorsed establishment of the hegemony.” While not an inaccurate reading of the film, Mookie’s action, thus interpreted, does not have the makings of a coherent synthesis of X and King. Lee noted the futility of the destruction, and Hurst notes that the act is based in hate. Neither Lee nor Hurst seems to be portraying X as an advocate of hateful futile violence. The violence condoned by Malcom X was explicitly “self defense”.

Perhaps Hurst is invoking panAfricanist Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Fanon suggests that the psychological damage rendered by institutionalized racism can be reversed through violent catharsis. This point of view is much more difficult to “synthesize” with King’s as it explicitly feeds “the downward spiral.”

Lee has claimed that the film is, indeed, a synthesis. But, as noted at the outset, filmmakers and films are subject to cultural forces that are not necessarily conscious or intentional. In Do the Right Thing, no particular ideology is valorized and no contradictions are synthesized.

Postmodernity and the Right Thing?

James Hurst suggests that Do the Right Thing represents the cinematic component of hip-hop culture. When his article was published (1990) very little had been written about hip-hop. Since that time, much work has been done and a number of illuminating theories have come to light. One of the explanations bandied about most is ‘postmodernism.’

Postmodernism continues to be the subject of much theoretical and political debate. Part of the problem is the free use of the term to designate phenomena as disparate as socio-historic-economic conditions and a species of critical inquiry. Moreover, as Jonathan Arac notes, the line between the theoretical and the political debates is unclear and thus, “to ‘have a position’ on postmodernism means not just to give an analysis of its genesis and contours, but to let the world know whether you are for or against it, and in fairly bold terms.” Many hold that postmodernism, in its resistance to metanarratives, signals the end of history and the death of politics. Luckily for the doomsayers, postmodernism still seems to lack any comprehensive theoretical paradigm. The best that we can do, according to Jim Collins, is address a series of recurring themes.

The key precondition for postmodernism is the bombardment of signs. Known as a semiotics of excess, postmodernism presupposes the proliferation of symbols and texts that we encounter in our mass-mediated urban world. Following from this condition are intertextuality and hyperconsciousness. Hyperconsciousness is the psychological response to/symptom of the proliferation. Intertextuality is simply the perceived presence of pre-existing or co-existing texts within an individual work. Both Do the Right Thing and hip-hop exhibit evidence of all of these themes. In any one hip-hop song, an almost infinite number of previously recorded songs may be digitally sampled. As we have seen, Do the Right Thing references a remarkable range of cinematic and musical styles while engaging in a political dialogue that precedes and surrounds the film. Advocates of postmodernism call this political/aesthetic system “bricolage”, while opponents call it “cannibalism.”

The most distinguishing, and most contentious, characteristic of postmodernism is its accommodation of multiple and contradictory “subject positions”. Advocates hold that postmodernism is the only critical theory capable of recognizing a spectrum of spectatorship. Assuming a relativist stance, postmodernism rejects both the hypodermic model of the subject (values directly injected into the spectator) and the “free will” notion (texts having no significant effect). Postmodern subjects position themselves within a text, based on any combination of social, cultural, aesthetic, moral or political factors. This supposedly accounts not only for multiple and contradictory readings of texts, but also for a text’s inherent contradictions.

Do the Right Thing is a film rife with contradictions. As a postmodern text, it displays no internal compulsion to somehow resolve them. Throughout the film, Mookie wrestles with relative subject positions (employee of Sal’s, big brother of Jade, father, and irresponsible child). Following the murder of Raheem, Mookie is forced by the crowd to “take a position.” Any course of action he follows will be “right” for only some of his multiple positions. When he throws the trash can, Mookie does what he feels is the most responsible thing possible, based on a negotiation between his feelings and his chosen subject position. It is no coincidence that his moment of decision coincides with a point of view shot that surveys the various proponents of his possible choices. It is at one and the same time the right thing and the wrong thing. Mookie is no hero and he enacts no brilliant synthesis of conflicting political stances. Rather, he is forced into an expression of conflicting identities.

Conflict, Generation X and Me

With all this talk about responsibility and subjectivity, I feel some compulsion to address my own “position”. 1989 was a year of major upheaval for me. As a white, middle-class male I had long considered myself a “liberal”, and subscribed to most of the beliefs that go along with that title. A nasty case of philosophical frustration combined with a number of congruent events to catalyze a major re-examination of my values along a less simple path. Do the Right Thing was part of that process. Long having professed a “zero tolerance” for violence, Do the Right Thing forced me to reexamine my position. I still don’t know where I stand on this issue, especially regarding experiences that I couldn’t begin to relate to. While I find the charges of anti-semitism, sexism, and homophobia levelled at Lee’s films irrefutable, I still must acknowledge Do the Right Thing as one of the reasons I am even able to comprehend these criticisms. Perhaps one of my own internal contradictions…

One of the first things that struck me about the film is how much it resembles the children’s television show Sesame Street. Lee’s visual construction of BedStuy virtually quotes the structure of Sesame Street. In fact the film’s whole aesthetic principle is reminiscent of the show, with musical interludes, speeches to the camera and so on. The general idea for this essay was sparked during a lecture on hip-hop, in which the speaker suggested that Sesame Street was a major aesthetic structural influence on hip-hop culture. Noting that Sesame Street was conceived as a positive response for children to the bombardment of signs, it struck me that any North American under the age of eight in 1968, including Lee, grew up watching the show. Ironically it’s probably the only common experience most of us have.

We are also of the generation labelled “X”, and although I have campaigned vigorously to try to shrug off this designation, several generalizations bear some relevance to this discussion. The “bombardment of signs” is almost a given for most of us. We have also borne witness to the failure/co-optation of the sixties’ counter-cultural movements. The conservative retrenchment seems to run deeper with each passing moment. Frequently, hopes for a more egalitarian society are superseded by questions of mere survival.

I don’t see our society’s deepest conflicts ever being resolved through compromise or victory for any side. I just hope we can survive the confrontations, and perhaps derive something positive from the differences. I’ve always understood Do the Right Thing to share this position. As DJ Mister Senor Love Daddy puts it:

My people, my people. Are we gonna live together? Together are we gonna live?

The Conceit of Postmodernity

I suggested above that postmodernist rhetoric often proclaims “the death of history,” thereby positing itself as “cutting edge” and historically unique. It is perhaps too easy to fall into this kind of egoism and proclaim that hip-hop, extreme alienation, and strange ways of coping with stylistic and ideological conflict are brand new and virtually unique unto people my age.

Consider hip-hop. Trisha Rose holds that the frequent digital sampling of older funk, soul and jazz records serves to situate the performer “within an Afro-American musical tradition, and a self-constructed resistive history”. This seems remarkably heritage-conscious for a postmodern form that supposedly resists “metanarratives”.

For that matter, the manner of coping with conflict discussed above existed prior to the postmodern age. Musicologist Peter Guralnick has suggested that:

the principals of (sixties soul music) brought to it such divergent outlooks and experiences that even if they had grown up in the same little town, they were as widely separated as if there had been an ocean between them. And when they came together, it may well have been their strangeness to each other, as well as their familiarity, that caused the cultural explosion.

Guralnick is positing soul music as a product of the interaction of individuals who are somehow conflicting and coalescing at the same time. This very “postmodern” aesthetic principle can be traced even further back. John Chernoff has found that African music uses “the multiple and fragmented aspects of everyday events to build a richer and more diversified personal experience”. It seems that postmodernism may not be so new after all.

Paradoxes

The fragmented identities and multiple subjectivities are considered by many to be a “negative” effect of postmodernism. But some Western cultural critics of African heritage have offered a very different assessment of the fractured postmodern identity. Stuart Hall writes:

Now that, in the postmodern age, you all feel so dispersed, I become centred. What I’ve thought of as dispersed and fragmented comes, paradoxically, to be the representative modern experience!…welcome.

Hall, a British-Jamaican, believes that his experience of dislocation is representative of many “migrants” to white-dominated, Western societies. As white society feels more and more fractured, Hall’s own fragmentation somehow becomes centred. Hall labels this a “paradox”.

I suggested above that our understandings of conflict, contradiction and resolution are frequently too narrow to accommodate the facts of our experience. We tend to attach the label, “paradox” when we encounter truths that we believe to be contradictory. Frequently, it is this type of encounter which forces us to re-evaluate our contexts of understanding. This situation has occurred many times in history. I have tried to show that African-derived musical traditions have tended to be structured such that they can accommodate contradictory truths. If, as suggested above, Do the Right Thing is the cinematic equivalent of hip-hop it should come as no surprise that it deals with its contradictory styles and ideologies by a “richer more diversified experience”.

Of course, European-derived intellectual systems have confronted paradoxes as well. However, we frequently put up some resistance. Many European biologists denied the existence of Australian animals because they believed that no creature can be both bird and mammal.

In the twentieth century we have confronted sciences that say light is both a particle and a wave (but not a compromise of particle and wave), multi-cultural cultures, and global villages. To point a finger at these phenomena and shout “incoherent” is to expose a limitation in our way of thinking. When examining the violence/non-violence debate and Do the Right Thing, the trick is not judgement, but rather, understanding.

I would like to thank Rob Bowman, Evan William Cameron, Sarah Demb, Jesse Hawken, Susan Lord, Lilian Radovac, and Robin Wood for their knowing and unknowing assistance with this paper.

References

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bordwell, David and Kirsten Thompson. Film Art: An Introduction. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993.

Cook, David. A History of Narrative Film. 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 1990.

Crouch, Stanley. “Do the Race Thing.” Notes of a Hanging Judge. Oxford: Oxford U P, 1990. pp. 237-244.

Davis, Thulani. “We Gotta Have It.” Village Voice. 20 June 1989. pp.67-72.

Eisenstein, Sergei. Film Form. New York: Harcourt, 1949.

hooks, bell. “Counter-Hegemonic Art.” Yearning: Race, Culture and Politics. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1990. pp. 173-184.

King, Martin Luther. Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Lightning, Robert K. “The Homophobia of Spike Lee.” Cineaction 29 (1992). pp. 35-39.

Powell, Kevin. “Spike Lee.” Vibe. Vol.2 No. 5 (1994). pp. 62-66.

Sklar, Robert ed. “Critical Symposium on Do the Right Thing.” Cineaste. Vol. 17 No. 4 (1990).

Stam, Roben et. al. New Vocabularies in Film Semiotics. London: Roudedge, 1992.

X, Malcom. The Final Speeches. New York: Pathfinder, 1992.

Zavattini, Cesare. “Some Ideas on the Cinema,” Film: A Montage of Theories ed. R.D. MacCann. New York: Dutton, 1966. pp. 216-227.

Author Affiliation

Ted Kulczycky is completing a Bachelor’s degree in Film Studies at York University and writes a regular column for Freewheelin ‘magazine. He continues to ponder the relationships of cinema, music and values.

Copyright Cineaction! 1996

Place of publication: Toronto

Country of publication: Canada

Publication subject: Motion Pictures

ISSN: 08269866

e-ISSN: 25622528

Source type: Magazine

Language of publication: English

Document type: General Information

ProQuest document ID: 216878568